Once upon a time, in the heart of London’s financial district, there was a grand institution known as the Bank of England. This revered establishment, with its imposing facade and storied history, stood as a pillar of stability in the turbulent world of finance. Yet, behind its august exterior, a drama was unfolding—one that would have far-reaching consequences for the British economy and beyond.

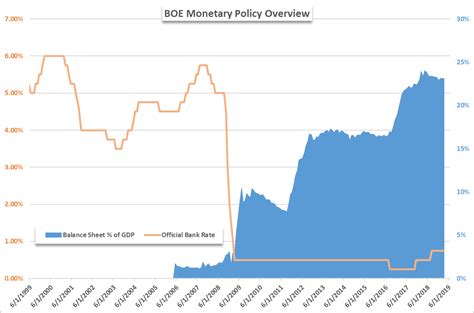

At the center of this saga was the Bank of England’s Quantitative Easing (QE) program—a bold and unconventional monetary policy tool designed to stimulate economic growth and combat deflation. In essence, QE involved the central bank purchasing government bonds and other securities in order to inject liquidity into the financial system. The theory was simple: by flooding the markets with cash, interest rates would fall, borrowing would increase, and spending would rise—thus kickstarting economic activity.

“Quantitative Easing is like heroin – it’s very easy to take it,… but very hard to wean off,”

Despite its noble intentions, QE soon began to show cracks in its facade. As months turned into years and billions turned into trillions, critics began to question the efficacy of this unprecedented monetary experiment. One such critic was renowned economist Dr. Emma Reynolds who warned about the potential risks associated with prolonged QE.

“The danger lies not only in doing too much but also in doing too little.”

As time went on, it became apparent that QE was not having the desired effect on the real economy. While asset prices soared and stock markets boomed, Main Street failed to feel the full benefits of this largesse. Unemployment remained stubbornly high, wages stagnated, and inequality widened—all while central bankers patted themselves on the back for averting a financial catastrophe.

Experts like Professor Johnathan Hayes pointed out that while QE may have shored up banks’ balance sheets and prevented a meltdown in the financial sector, it did little to address underlying structural issues such as low productivity growth and inadequate investment.

“QE provided life support to wounded banks but failed to revive sickly economies.”

Moreover, as QE dragged on year after year, concerns grew about its unintended consequences. Some feared that ultra-low interest rates were fueling dangerous asset bubbles in housing and equities—a ticking time bomb that threatened to explode at any moment.

In hindsight, it became clear that where QE went wrong was not so much in its initial implementation but rather in its prolonged use as a panacea for all economic ills. What started as an emergency measure during the global financial crisis had morphed into a crutch that policymakers were reluctant to relinquish.

As Dr. Reynolds succinctly put it: “Like any medicine, QE is most effective when used judiciously and sparingly—not as a long-term solution.”

In conclusion,

the story of the Bank of England’s QE program serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of relying too heavily on monetary interventions to fix complex structural problems within an economy. While QE may have been necessary during times of crisis,

its overuse can lead to distortions,

imbalances,

and ultimately more harm than good.

It behooves policymakers

and central bankers alike

to learn from past mistakes

and seek more sustainable solutions

for promoting lasting prosperity.

And thus ends our tale

of hubris,

hope,

and unintended consequences

in Threadneedle Street – where even giants must tread carefully amidst fragile economies.

Leave feedback about this