Have you ever stopped to think about dung as more than just a smelly substance left behind by grazing animals? It turns out that manure, yes, dung, can provide valuable insights into our environment and the distribution of herbivores globally. Let’s embark on a journey into the fascinating world of dung data.

Picture this – vast drylands covering about 40% of our planet’s land area. In these arid and semi-arid regions, livestock and native grazing animals roam, leaving behind traces of their presence in the form of dung. Recently, an international team led by Professor David Eldridge from UNSW Sydney delved into the realm of dung research to create the very first global assessment of dung production by these animals.

According to Prof. Eldridge, understanding where herbivores are located is crucial for various reasons. He explains,

“It helps us improve our grasp on the grazing industry and disease spread among animals.”

The team discovered intriguing patterns – livestock and wild herbivores seem to have their own preferred territories on Earth. This insight could revolutionize how we approach land management practices tailored to specific animal habitats.

But how do researchers pinpoint areas teeming with herbivores without physically counting each animal? Traditional methods rely on environmental indicators like rainfall and temperature to estimate livestock density crudely. However, Prof. Eldridge proposed a novel approach – using dung as a proxy for animal distribution.

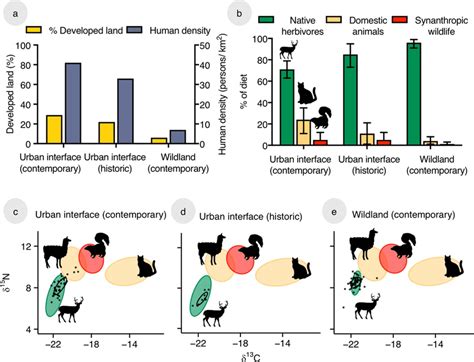

By analyzing 50 global datasets encompassing dung mass and grazing pressure from diverse herbivores such as antelopes and kangaroos, the team uncovered a strong correlation between dung production and animal presence. This revelation paved the way for generating detailed maps showcasing hotspots of dung production worldwide.

Surprisingly, when comparing native herbivores’ territories with those of livestock, researchers identified both overlap and distinct zones where these animals coexist separately. This separation could result from factors like resource competition or wild herbivores avoiding potential diseases transmitted by domesticated animals.

The significance of assessing livestock distribution extends beyond mere curiosity; it plays a pivotal role in land use planning, predicting meat production trends, estimating methane emissions, and enhancing food security strategies globally. Dung emerges as an unexpected hero in this narrative – offering a reliable method for gauging animal densities more efficiently than traditional surveys.

Prof. Eldridge emphasizes that studying dung not only aids in understanding large-scale habitat preferences but also benefits farmers at local levels by informing strategic decisions on infrastructure placement for optimizing livestock productivity. Despite challenges like human collection of dung or rapid decomposition processes in certain regions impeding accurate assessments, robust relationships between dung quantities and grazing pressure persist.

In conclusion, this groundbreaking research opens new doors for incorporating dung data into existing models and maps related to livestock management worldwide. Who would have thought that something as humble as dung could hold the key to unraveling mysteries about our planet’s herbivores?

Leave feedback about this